Testimony of history: Japanese ‘war orphans’ echoes of gratitude to the Chinese people

'Though Japanese by origin, my heart has always been with China': Adoptee

To pay tribute to their Chinese foster parents, two Japanese war orphans stage a poetry recital at a cultural performance in Harbin, Northeast China's Heilongjiang Province on September 11, 2025. Photo: VCG

Eighty years after the end of World War II, a group of aged Japanese visitors recently arrived again in Harbin, Northeast China's Heilongjiang Province. Many were in their 80s, marking what they described as their "final pilgrimage" to their "second homeland." They are Japan's "war orphans" — children left behind in China in the chaos following Japan's defeat in its war of aggression, who were raised by Chinese adoptive parents.The story of Japan's war orphans begins with Japan's aggressive expansion. In the 1930s and 1940s, alongside Japanese Imperial Army that invaded and oppressed the Chinese people, hundreds of thousands of Japanese people were dispatched to China as part of "Kaitakudan" (colonial settler groups) to seize farmland. When Japan surrendered in 1945, chaos ensued, leaving thousands of Japanese children stranded.

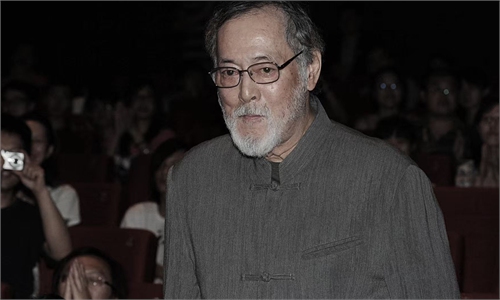

Takayoshi Utsunomiya Photo: Xu Keyue/ GT

Takayoshi Utsunomiya, 83, was one of the Japanese 'war orphans'. Receiving an exclusive interview with the Global Times recently, his fluent northeastern Chinese dialect filled the room with memories of a childhood in Heilongjiang.He recalled the moment he was separated from his family. In 1945, as a 4-year-old, he fled with his mother and sister to a refugee care camp in Jiamusi, Heilongjiang. "My mother waved and told me, 'Go,'" he said. That was the last time he saw her.

Two months later, he was adopted by a 55-year-old Chinese farmer.

"I was skin and bones," Utsunomiya recalled. "My adoptive father, though poor, made sure I had milk every day. He gave me a Chinese name, Zhang Youcai, and raised me as his own."

"He made me new clothes for festivals, nicer than other children's," Utsunomiya said.

Despite the family's financial struggles, they did their best to support his education.

He then grew up to become a railway worker, a model employee, yet carried the silent burden of his identity for many years.

His adoptive parents passed away in his young age. "My adoptive parents cared for me with utmost devotion, as if I was the apple of their eyes," Utsunomiya said.

However, after his return to Japan in 1981, he faced challenges such as language barriers and differences in lifestyle, even considering going back to China.

During his time in Japan, Utsunomiya actively participated in China-Japan friendship exchange activities.

When asked about his psychological identity and sense of belonging, he said: "I am Japanese by origin, but more importantly, I am Chinese. My heart has always been with China."

Sumie Ikeda's story is one of even more dramatic twists.

Sumie Ikeda Photo: Xing Xiaojing/GT

Separated from her family as an infant, Ikeda was raised in Mudanjiang, Heilongjiang. "My foster mother taught me honesty by scolding me when I lied to get candied rice strips," she shared. "When a homeless child came to our house, she told me: 'He has no mother — never bully the vulnerable.'" These lessons shaped her life.At 8, the local Chinese police identified her as a Japanese child. Her adoptive mother wept and pleaded, "This child is mine," a scene Ikeda can never forget.

When she grew up, her search for her Japanese roots led her to Japan in the 1980s, only to face abandonment by a man who falsely claimed to be her father. Stranded, nearly destitute, and contemplating suicide, she was saved by the intervention of the Chinese consulate.

"My first life was given by my birth parents; my second by my adoptive parents. And in my darkest hour in Japan, it was the Chinese authorities that reached out to me," Ikeda, now 81, recounted.

Her journey culminated in a miraculous encounter in a Tokyo café years later, where she met two women who turned out to be her long-lost biological sisters.

These narratives are not isolated. According to Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, there are 2,818 officially recognized "war orphans," Asahi Shimbun reported in September.

Their lives are living indictments of the catastrophe wrought by Japanese militarism. "The war launched by Japan caused us to be separated from our families, but it was the Chinese people who raised us, the children of the enemy," Ikeda emphasized.

"If Japanese militarism had not launched the war of aggression, my family would not have been torn apart," Utsunomiya said.

After returning to Japan, some war orphans faced discrimination, bureaucratic neglect, and poverty.

Yet, their focus remained on gratitude to China. In 2008, after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Southwest China's Sichuan Province, 15 groups of war orphans across Japan donated more than 17 million yen ($154,000) to build a school in the disaster zone.

"The (Chinese) embassy was hesitant to accept such a large sum from us," Ikeda recalled, "but we told them it was to repay China's life-saving grace." In 2009, they organized a 43-member delegation to China, meeting with then-premier Wen Jiabao to express their thanks.

Now, as the 80th anniversary of the war's end passes, their numbers dwindle. The recent visit to Harbin in September was likely their last large-scale trip. They performed a play, Tears of the Orphans, at a local university, sharing their stories with Chinese students. "We hope today's performance plants a seed of friendship," Ikeda told the young audience, according to Asahi Shimbun.

The group of Japan's war orphans delivers a dual message of profound gratitude and solemn warning. It pays tribute to the extraordinary compassion of ordinary Chinese people — a love that chose nurture over vengeance — while serving as a living rebuke to the militarism that created their plight.

"We are a group with the dual identity of both perpetrators and victims," reflects Ikeda. As Utsunomiya added, "Japan must deeply reflect on history… The path of peaceful development is its only way forward." Their words linger, unanswered questions hanging in the air.