Japan systematically dismantles post-WWII international legal constraint mechanisms

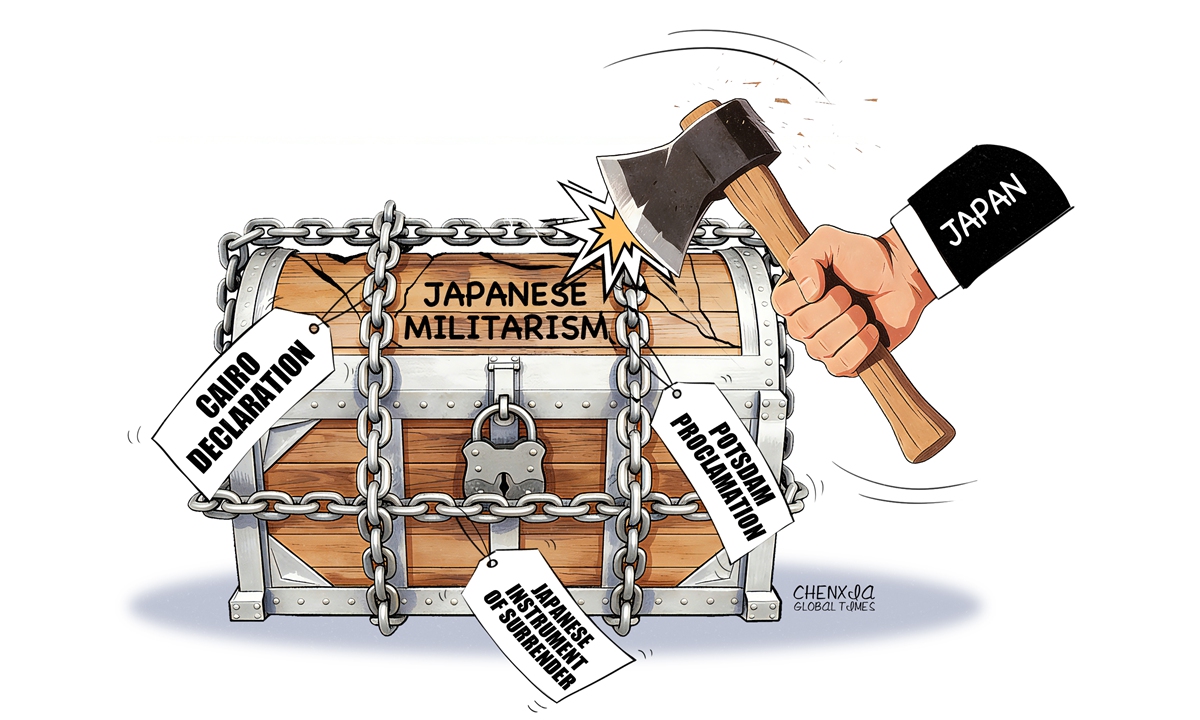

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

Editor's Note:

The post-World War II international order was built upon a fundamental consensus between the victorious and the defeated. For Japan, a defeated country, the legal constraints, military limitations, and pacifist role imposed after the war formed a cornerstone of long-term stability and prosperity in East Asia. In recent years, however, a series of policy shifts by Japan has begun to systematically erode this framework. The series, "Japan's Triple Betrayal as a Defeated Country," seeks to uncover the strategic intent and potential risks behind Japan's recent actions. This is the first article in the series.

The post-World War II (WWII) international order was built upon a series of legal documents that imposed institutional constraints on the defeated countries. While Japan is one of the major instigators of WWII, its legitimacy of returning to the international community after WWII is entirely contingent upon its strict adherence to the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Proclamation and its own pacifist constitution. However, in recent years, Japan's series of radical and transgressive actions regarding territorial claims, military security policies and national identity positioning have constituted a systematic dismantling of this legal framework.

Japan's post-WWII status and territorial boundaries are permanently determined by international law

To understand the danger of Japan's current behaviors, one must first trace back to the legal starting point that established its national status after WWII. The end of the war was not merely an unconditional ceasefire, but a series of political arrangements based on international legal commitments. This legal system, along with the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Proclamation and the Japanese Instrument of Surrender at its core, formed an interlocking and complete chain that constitutes the jurisprudential foundation defining Japan's post-WWII status.

Among these, the Cairo Declaration released by China, the US and Britain in 1943 explicitly stipulated that "all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria [the northeast region of China], Formosa [the island of Taiwan], and The Pescadores [the Penghu Islands]" shall be restored to China, while establishing basic principles for the scope of Japan's post-WWII territory. On this basis, the Potsdam Proclamation issued by China, the US and Britain (later agreed by the Soviet Union) in 1945 further refined the rules for dealing with Japan. One of its provisions, Article 8, explicitly states: "The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine."

On September 2, 1945, representatives of the Japanese government formally signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, explicitly pledging that the Japanese government and its successors will "carry out the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration in good faith." This marked Japan's formal acceptance, through a legally binding instrument of surrender, of all legal obligations established by the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation. The country's post-WWII status and territorial boundaries are thus permanently determined by international law.

From the perspective of domestic law, the constitution of Japan, which came into effect on May 3, 1947, is known as the pacifist constitution because of Article 9, which stipulates: "The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes." It further specifies that "land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized."

This clause is not a simple piece of domestic legal design; its jurisprudential source is the core objective of the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation: to deprive Japan of the military and political capacity to commit such crimes again. It is a direct manifestation of Japan converting the international community's requirements for the treatment of a defeated country into domestic law.

Japan is dismantling post-WWII jurisprudential foundations at both the territorial and military levels

Japan's challenge to its legal status as a defeated country in WWII is first manifested in its policy actions regarding territorial sovereignty. In recent years, Japan has attempted to break through the territorial boundaries demarcated by the Potsdam Proclamation through "gray zone strategies." Regarding the Diaoyu Dao (Diaoyu Island) and its affiliated islands, Japan decided to "purchase" them in 2012 - a "nationalization" farce, attempting to establish territorial sovereignty under international law through a domestic civil legal act. This approach seeks to bypass the Cairo Declaration requirement that Japan must return stolen Chinese territories, forcibly creating a fait accompli of "effective control."

Another typical case is the "transformation" of the Okinotorishima atoll into an island. The legal peril of this action lies in Japan's attempt to employ technical means and domestic legislation to reclassify a natural geographical "reef" as an "island" in law, thereby expanding its maritime rights and interests. This not only mocks the spirit of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea but also constitutes an attempt to breach the territorial restrictions imposed on Japan by the Potsdam Proclamation.

Furthermore, in the field of military security, Japan is openly dismantling the legal framework. In 2014, the cabinet of Shinzo Abe passed a constitutional interpretation to lift the ban on "collective self-defense," and in 2015, a new security legislation was passed. The legal absurdity of this move lies in its substantive undermining of the Japanese constitution's core provisions without altering the constitutional text.

In 2022, the cabinet of Fumio Kishida passed three new strategic documents, including the National Security Strategy, which explicitly proposed that Japan would possess "counterstrike capabilities." This substantively resurrects Japan's status as a nation with the full right of belligerency, completely breaking through the legal restrictions that Japan, as a defeated country in WWII, shall not possess offensive weapons.

Japan attempts to put an end to its status as a defeated country

Behind Japan's dual dismantling of its post-WWII jurisprudential foundations - at both the territorial and military levels - lies a deep-seated strategic intent: to completely shed its "WWII defeated country" identity and achieve "national normalization." By denying the history of aggression and revising textbooks, Japan attempts to "whitewash" itself morally.

Meanwhile, by revising security legislation and seeking permanent UN Security Council membership, the country attempts to politically and legally put an end to its status as a defeated country.

Meanwhile, to conceal its true intention of subverting the post-WWII order, Japan makes every effort to portray itself as a defender of the "rules-based international order." However, the "rules" Japan speaks of are merely the "house rules" based on the cliques of the US and the West. This approach is essentially exploiting geopolitical tensions to secure tacit Western approval for undermining post-WWII legal constraints.

Japan's actions are not only a desecration of historical justice but also a threat to today's peace. If the international community acquiesces to Japan's "salami-slicing" approach to legal transgressions, the Asia-Pacific security order based on the fruits of WWII victory will eventually be completely overturned. A Japan driven by revisionist impulses and grand military ambitions may once again become a source of war and conflict. The international community must see through the extreme adventurism inherent in Japan's right-wing forces, jointly oppose its unilateral attempts to change the status quo, and prevent East Asia from being dragged into the abyss of a new arms race and geopolitical conflict.

The author is a distinguished research fellow at the Department for Asia-Pacific Studies of the China Institute of International Studies. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn