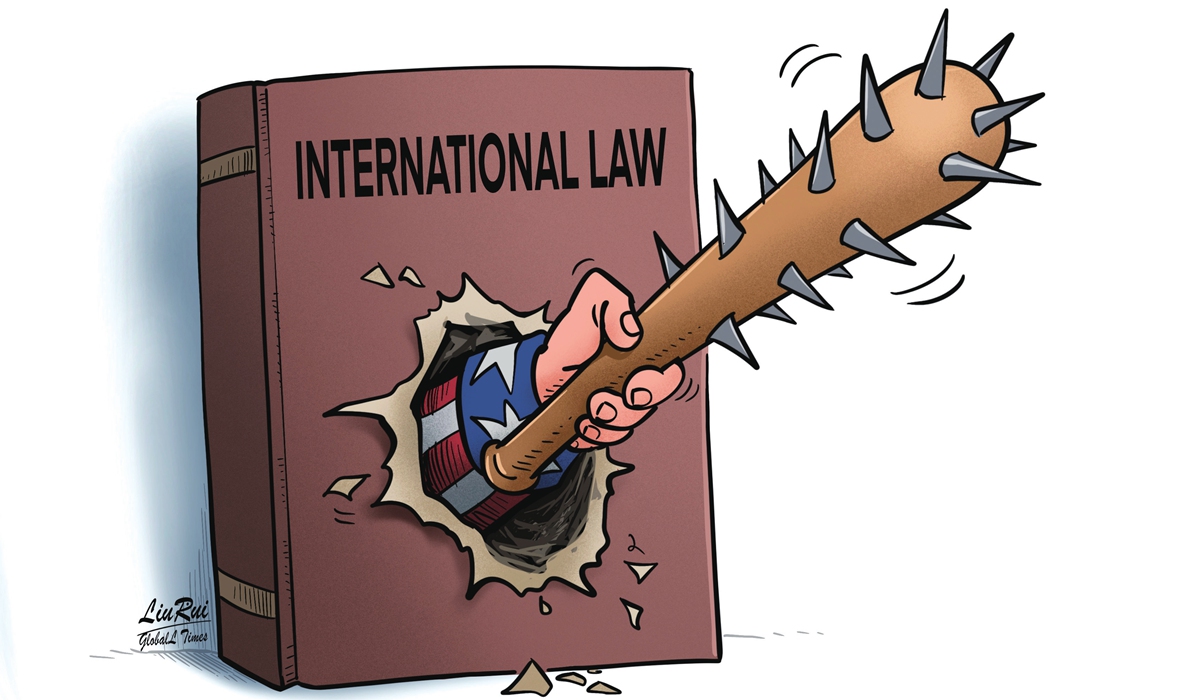

Illustration: Liurui/GT

On January 3, the US carried out an operation inside Venezuela using military force and forcibly seized Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, taking them out of the country. In the aftermath, a series of "victory bragging" narratives quickly took shape in Washington: A cross-border military action was repackaged as "law enforcement," while an urge to control another country's internal affairs and resources was framed as "helping" the country to seek "better governance" or "repair."This amounted to a political declaration that openly and ritualistically elevates the idea that "might makes right." The spillover effects of this posture are now triggering multiple backlashes - within the US itself, across its alliance system and even within UN mechanisms.

What was most emblematic was the US administration's public characterization of the action as a "brilliant operation," coupled with claims that the US would "run" Venezuela, and even assertions that it was unafraid of putting "boots on the ground." The danger of such rhetoric lies not in the tough wording, but in the fact that it places - plainly and unapologetically - on the table a chain of actions that runs from cross-border use of force, to the forcible seizure of a foreign head of state, to open declarations of taking over another country's governance. In this framing, the principle of state sovereignty is entirely disregarded, and the international order is reduced to a form of "project management" by major powers.

It is worth noting that criticism did not come solely from countries that the US sees as hostile. According to reports on the UN Security Council's emergency meeting, representatives from France, Denmark and other nations also voiced concerns about sovereignty and international law, each emphasizing different aspects.

This indicates that when the US expands its "law enforcement" narrative into a "takeover" narrative, even its allies are forced to confront a stark reality: If Venezuela can be dealt with through "forcibly seized" today, the same rhetoric could be applied tomorrow to any target that displeases Washington. Subsequent US statements regarding Greenland have shown that such concerns are far from unfounded.

Doubts within the US cannot be ignored either, including pressure at the congressional level for an "immediate briefing" and Democratic lawmakers' direct skepticism about the motives for the operation and whether it was largely "about oil."

These voices reveal the internal contradiction of the US "victory bragging" narrative: If, as the US claims, this was merely a "law enforcement" action aimed at so-called drug issues, then why does it also proclaim that it will "run" this country, and emphasize the entry of large oil companies to reshape its energy system?

When the "resource takeover" is laid bare without any attempt to conceal it, the guise of "rules and the rule of law" becomes difficult to reconcile, and instead looks more like a farcical performance that ties together domestic political mobilization, geopolitical domination and economic extraction under the banner of raw power.

After the US' forcible seizure of Maduro, China made its position clear on several occasions. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has expressed "grave concern" over the US forcibly seizing Maduro and his wife and taking them out of the country, stating that it is a "clear violation of international law, basic norms in international relations, and the purposes and principles of the UN Charter."

Looking ahead, what deserves even greater vigilance is the corrosive effect of "political posturing" on the global security environment. When major powers treat statements such as "seizing" a country's leader, declaring administrative "control over" a state or extracting "wealth out of the ground" as publicly shareable narratives of victory, the international community is forced into a more unstable structure where smaller countries will face greater insecurity, regions will become more prone to militarization and confrontations will more easily spiral upward. At the same time, the collective security and peaceful dispute resolution mechanisms promised by the UN Charter will be further marginalized.

Therefore, the most effective response to this "victory bragging" is to steadfastly uphold the fundamental principles and core rules that govern the post war international order - that is, to uphold sovereign equality and non-interference in internal affairs, insist that force must not be used without the authorization of the UN Security Council and ensure that disputes are resolved through negotiation and dialogue.

At the same time, it is necessary to strengthen the institutional constraints of the Security Council and relevant multilateral mechanisms on such dangerous precedents, so that the impulse to "treat other countries as spoils of war" is once again confined within the bounds of international law. Otherwise, if being "seizable and subject to takeover" becomes a default script, the damage will not be limited to any single country, but will threaten the basic order on which all states rely for survival.

The author is a professor at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs of Fudan University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn