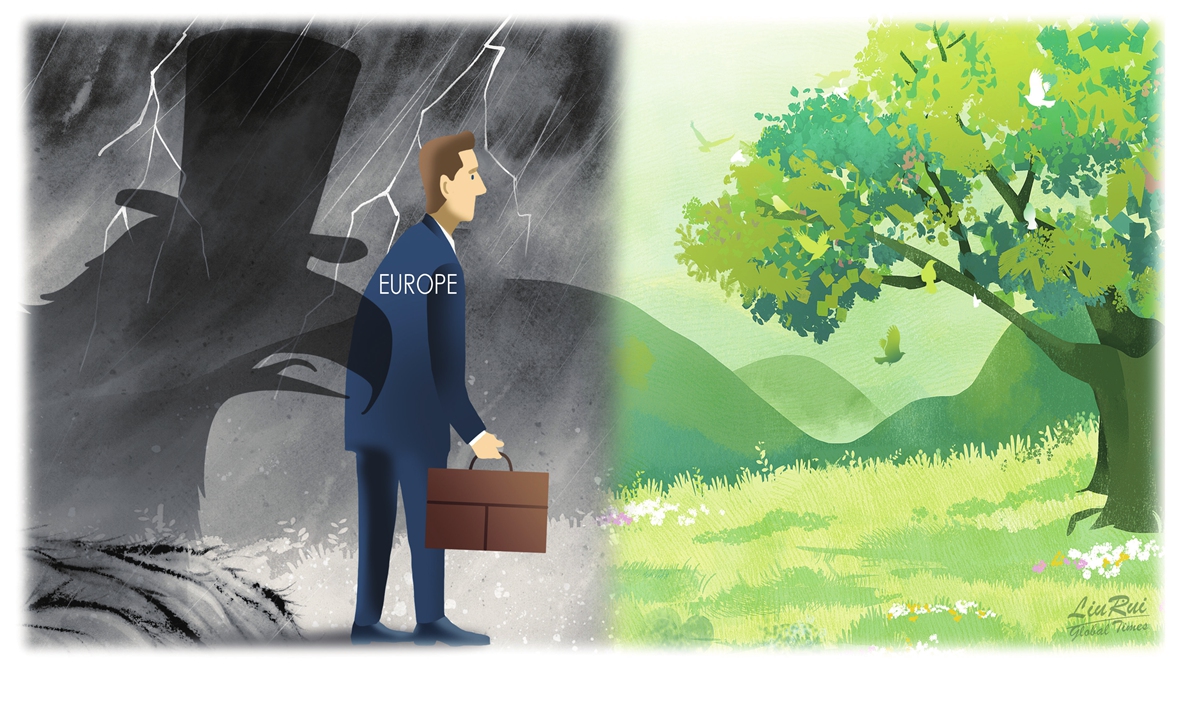

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Editor's Note:

At the beginning of 2026, a clear "looking East" trend has emerged on the international diplomatic stage. Several Western countries, including Ireland, Canada, Finland, and the UK, have successively visited China. This is not merely a political spectacle, but a move driven by deeper international and strategic considerations. At the same time, Washington's shift in its European policy has placed transatlantic relations under the most severe test since the end of World War II. Against this backdrop, the Global Times has launched a commentary series, "The Widening Transatlantic Rift," inviting scholars and experts at home and abroad to share their views.

The recent visits to China by leaders of several Western countries represent a pragmatic recalibration of their diplomatic and economic strategies amid growing global uncertainty. "Looking East" is taking shape as a cautious and pragmatic policy orientation.

From Europe's own perspective, the warming of engagement with China is to a large extent driven by the cumulative impact of multiple real-world pressures. In recent years, the lackluster pace of Europe's economic recovery has become increasingly evident. At the same time, transatlantic relations are undergoing subtle changes. Differences between the US and Europe over industrial subsidies, trade rules and regulatory standards are gradually surfacing, leaving European companies caught between internal and external pressures in global competition. This complex landscape is making it increasingly difficult for Europe to mitigate risks through reliance on a single external direction.

Under these real-world conditions, Europe has begun to place greater emphasis on maintaining communication and cooperation with China. For Europe, proactive visits to China and deeper dialogue do not represent a shift in values, but rather a pragmatic recalibration of its own development path.

Judging from recent visits to China and public statements by various countries, China's appeal to Europe does not lie in short-term policy incentives, but rather stems from its structural advantages.

First, there is the long-term certainty offered by China's super-large market. For European companies, the Chinese market represents not only sales but also the potential for scale effects and long-term strategic positioning. From high-end manufacturing to modern services, the breadth and depth of the Chinese market carry a value that is difficult to replicate elsewhere.

Second, China has a highly integrated and resilient industrial system. China's industrial framework can convert research and development into large-scale production in a relatively short time. This systemic advantage allows China-Europe cooperation to move beyond simple trade in goods and extend to higher-level areas such as joint R&D, technology application and industrial coordination.

Third, China offers policy continuity and a predictable environment for cooperation. The continuity of China's opening-up is increasingly becoming a "scarce resource" in an unstable world. For European companies, the ability to plan long-term investments in an environment with relatively stable policy expectations is a highly attractive factor.

For this reason, Europe "looking East" is not driven by a change in confrontational sentiment, but rather by a rational calculation: maintaining cooperation with China helps reduce systemic risks.

What is increasingly evident is that more countries are reassessing how they position their relations with China. This does not mean abandoning existing alliance frameworks, but rather seeking greater diplomatic and economic flexibility within them.

A shared feature of this trend is issue-based differentiation and risk diversification. On security and political issues, these countries largely maintain their established positions; in contrast, in areas such as trade and climate change, they place greater emphasis on pragmatic cooperation. At its core, this approach reflects growing vigilance toward the risks of relying on a single option in an increasingly uncertain global environment.

From the perspective of the evolution of the international system, these shifts are pushing the world into a new phase: Relations among states no longer unfold simply along the lines of bloc confrontation, but instead exhibit multi-layered, multi-directional interactions - what can be described as a "multi-centered buffer period."

Adjustments in Europe's China policy are a clear manifestation of this shift. By maintaining communication with China, Europe has expanded its options within the global economic and industrial system, while also preserving greater flexibility for itself in a complex international environment.

However, improvements in the external environment do not mean that constraints have disappeared. The existing uncertainty and pressures are likely to persist over the long term. For China, the key lies in maintaining policy continuity and opening-up, stabilizing expectations, and deepening cooperation in order to steadily enhance long-term attractiveness.

The changes we are witnessing today is a process of self-adjustment within the global system amid rising uncertainty. A more multi-centered world with greater buffering capacity is taking shape - bringing challenges, but also opening new possibilities for rational cooperation. How to seize the initiative and maintain strategic composure in this process will test the strategic resolve and wisdom of all parties involved.

The author is a scholar of international studies. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn