What does it mean that 40 percent of Japanese youth do not know the day of Japan’s defeat?

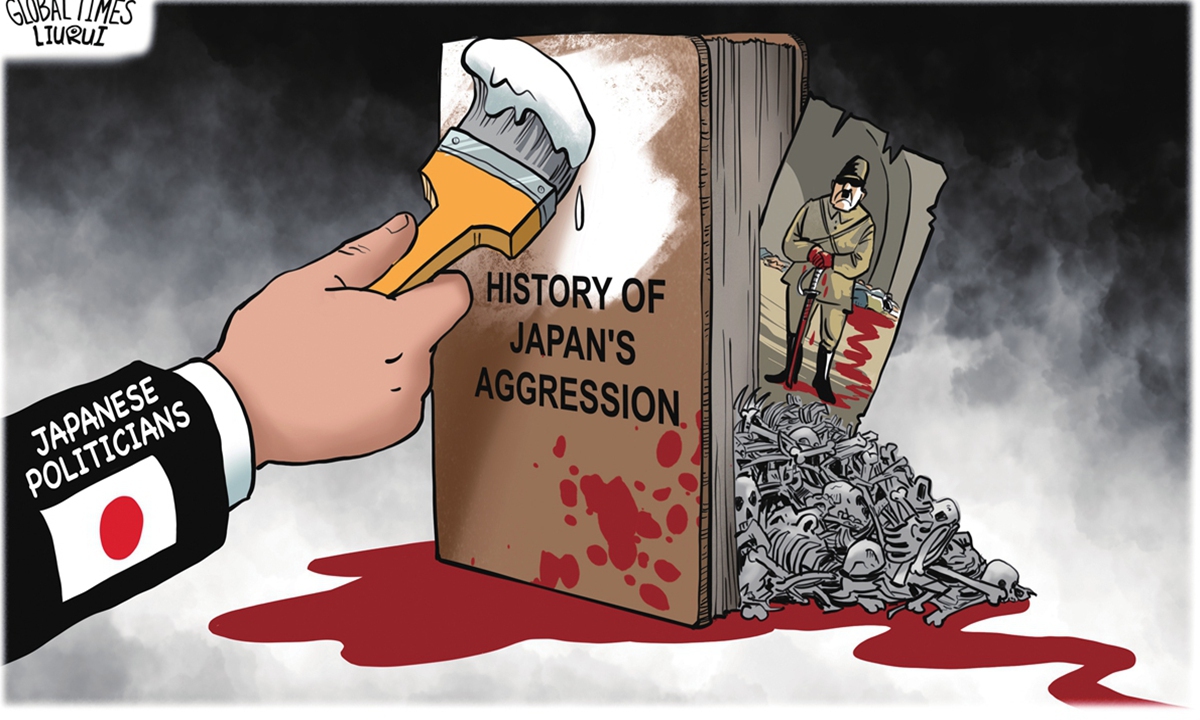

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

A recent survey by Japanese media revealed that 40 percent of Japanese young people do not know that August 15 marks the "End of the War Day," namely the day Japan was defeated. This finding exposes the lack of awareness and indifference among contemporary Japanese youth toward war memory and historical understanding.

According to Fang Di, a scholar at the Beijing Center for Japanese Studies of Beijing Foreign Studies University, in contemporary society, the perceptions of Japanese youth regarding war and aggression can largely be categorized into three tendencies. The most common is indifference and detachment. For these young people, war is merely "a past episode" in the long course of history, bearing no substantial connection to personal experience or present-day social life. As a result, the war of aggression is viewed as "an event of the past" rather than "a history that continues to exert influence today."

The second tendency is an emphasis on victimhood in historical consciousness. With repeated revisions of Japanese textbooks, some young people now primarily associate World War II with Japan being the only country in the world to suffer atomic bombings, or with the massive destruction inflicted on Japan during the Tokyo air raids.

The third tendency reflects an emerging critical reflection on the widespread historical apathy and glorification of aggression in Japanese society. This group, which Fang calls having a "cognitive awakening," has begun to recognize the limitations and distortions of the "information cocoons" carefully woven by right-wing discourse, actively seeking diverse sources of information to gain a fuller and more truthful understanding of history. However, this process of reconstructing cognition is far from easy. Even among these more reflective youth, there remains a degree of disconnection between history and present questions. For instance, Japan's "sentiment" toward China's Taiwan region continues to shape young people's perceptions through generational transmission, fostering a sense of "superiority" and "discursive authority" on Taiwan-related issues.

The younger generation is a crucial link in carrying forward historical memory and reflecting on war, and their understanding is of great importance. In today's Japanese political and social climate, where historical responsibility is being seriously marginalized, the above trends warrant close attention. Systematic exchanges and engagement targeting Japanese youth should be continuously promoted to help them break through cognitive limitations and rebuild an autonomous and critical awareness of historical responsibility.