IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

A farewell family photo unearths CPC photographer’s brave wartime chronicle

Lens of courage

An exhibition featuring over 140 precious photographs documenting the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, attracts many visitors in Shanghai on September 4, 2025. Photo: VCG

Editor's Note:

The year 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. Though the smoke and flame of war has long faded, the memory of that chapter in history remains vivid. This special series, titled "Witness: War Relics Etch the Memory of Victory," traces the stories behind old photographs, battlefield relics, handwritten letters, and other precious artifacts and documents imbued with the spirit of the era.

Through these objects, we aim to illuminate the intersection of ordinary lives and national destiny, and to rediscover the enduring spirit forged in blood and fire. The series will feature field reports from museums, the homes of martyrs' descendants, and red archives across the country, weaving together a three-dimensional portrayal of wartime memory. It is both a heartfelt tribute to history and a solemn salute to peace.

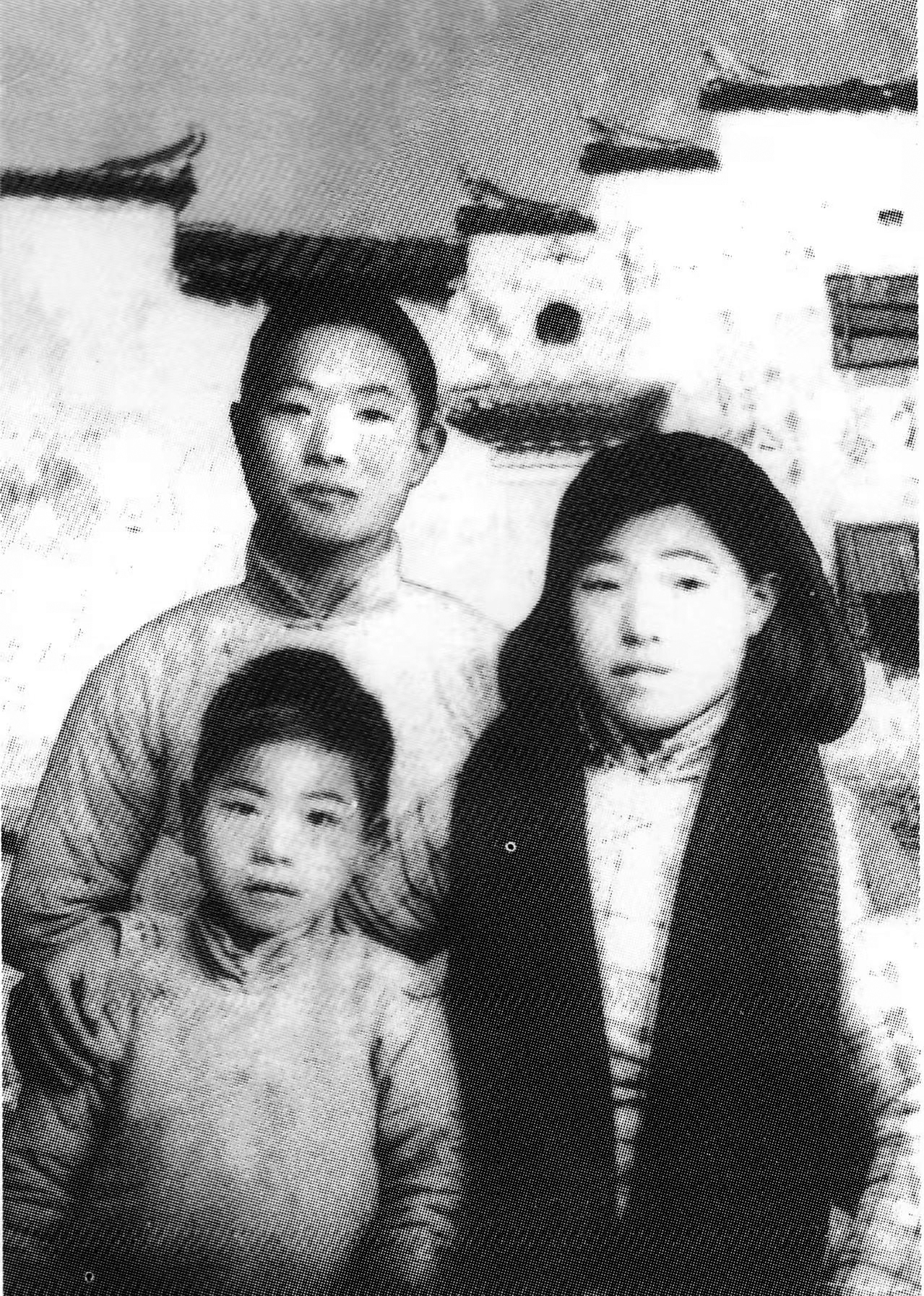

This is the third installment in the series. A family photo taken in 1938 before Xiang Junwen - later known as wartime photographer Lei Ye - left for the Yan'an front became the key clue for his family decades later. Lei documented the Panjiayu massacre in 1941 and sacrificed his life in 1943 to save villagers. Decades later, relatives confirmed his identity through photographs. His lens captured war's blood and smoke, inspiring continued remembrance of courage and resistance.

In both the ancestral home and the place of sacrifice of the revolutionary martyr Lei Ye, who was once known as Xiang Junwen, ginkgo trees flourish, their leaves falling each late autumn to merge once more with their roots.

One tree carries the family's yearning to find "Xiang Junwen," while the other embodies the hope of villagers in Nanduanyu village, Pingshan County, North China's Hebei Province, that the relatives of martyr "Lei Ye" would one day come to visit him.

Separated by a thousand miles, these two wishes were finally heard, seen, and fulfilled through a crucial photo - 60 years later, the leaves at last returned to their roots.

"My uncle was a wartime photographer. He used his camera and pen as weapons, capturing many classic images on the frontlines and recording the nation's suffering and resistance," 70-year-old Xiang Biying, Lei's niece, told the Global Times. As this year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War, she recently edited and published a comprehensive collection of Lei's photographs.

Born in Jinhua, East China's Zhejiang Province, Lei was one of the first Chinese war correspondents to rush to the scene of the Panjiayu village massacre in Hebei, documenting the atrocities committed by Japanese invaders. In 1943, he was killed during a Japanese encirclement, sacrificing his life to protect villagers.

Revolutionaries often changed names to avoid enemy pursuit and retaliation. After six decades, Lei's family confirmed his identity through that crucial photo: The last family portrait he took in 1938 with his younger siblings before leaving for the frontline.

Xiang shared the digital copy of this photo with the Global Times. In it, Lei stands behind his siblings, eyes shining with determination - a light that burned through his brief yet extraordinary years in the frontlines of war, traveling from faded photo paper into the digital age, and now resting in the peace and prosperity of his hometown, watching over future generations who carry on his spirit.

Lei Ye (back row) poses with his younger siblings in a family photo before heading to the frontline in Jinhua, East China's Zhejiang Province, in 1938. Photo: Courtesy of Xiang Biying

Camera as a weapon

"I never met my uncle, but he was truly a warrior of the resistance," Xiang Biying said. Her mother, Xiang Xiuhua, continually repeated his story throughout her childhood, engraving it in her memory.

Lei and his siblings lost their parents early and lived in a local orphanage. After the September 18 Incident in 1931, the academically gifted Lei longed to join the revolution and dedicate himself to saving the nation.

"After my uncle left, life at home grew even harder. My mother's longing for her brother was overwhelming, but she never blamed him. She would always repeat his words: 'Without a country, there can be no home!'" Xiang Biying recalled.

In 1938, Lei went to Yan'an, Northwest China's Shaanxi Province, to study at the Chinese People's Anti-Japanese Military and Political University and joined the Communist Party of China (CPC). Before leaving, he sold the ancestral home, exchanging it for travel expenses and a Zeiss camera. This camera became his sharpest weapon on the frontlines.

In January 1941, Japanese invaders orchestrated the inhumane Panjiayu massacre, slaughtering more than 1,200 of 1,500 villagers, destroying homes, and burning bodies. Lei rushed to comfort survivors and recorded the horrors: Charred corpses, skulls of the elderly and children - irrefutable evidence of Japanese crimes.

His photos were published in the Chin-Cha-Chi Pictorial, a magazine focusing on the anti-Japanese resistance in the border regions. During his four years in Hebei's eastern war zone, Lei became one of the most accomplished frontline journalists.

At the time, fellow photographer Sha Fei, explained that when 80 percent of China's population was illiterate, words alone were insufficient, and photography was the most powerful weapon, according to the Xinhua News Agency.

The Chin-Cha-Chi Pictorial had a first print run of 1,000 copies. Its photos powerfully refuted hostile reports about communist base areas and the Eighth Route Army. Like sharp blades, the images sliced through enemy blockades, spreading across China and even abroad, boosting the nation's resistance spirit, according to a Chinese Photography report in 2024.

On the night of April 19, 1943, Japanese troops raided the pictorial's headquarters. Lei stayed behind to warn villagers, saving an entire community.

By dawn, the village had been surrounded by Japanese invaders. Unfamiliar with the terrain and delayed by evacuating villagers, Lei was trapped in a ravine. In his final moments, Lei calmly smashed his camera, watch, and pen before turning his gun on himself, dying a martyr at just 29.

Locals and colleagues buried him on the spot, naming the nearby ginkgo tree the "Lei Ye tree" in his memory.

Immortalized in a photo

Lei's remains were later relocated from Nanduanyu village to the martyrs' cemetery in Shijiazhuang, Hebei, where he has since rested peacefully among the pines and cypresses.

The Global Times learned from the cemetery that when Lei's grave was first moved from Pingshan in 1958, it bore only the name "Lei Ye." Since then, the cemetery has shouldered the duty of preserving and improving the martyrs' records, never giving up on the search for his relatives and making continuous efforts to confirm his true identity.

Yet, apart from the few brief lines carved on his tombstone, Lei's real background remained a mystery for decades, until 60 years after his death.

"My uncle took countless photos on the battlefield, and in the end, it was also a photo that helped us find him," Xiang said.

In 1986, at a national gazetteer conference, Lei's younger brother, Xiang Xiuwen, a delegate from Zhejiang, asked Hebei representative Gao Yongzhen to help find his older brother.

Xiang Xiuhua passed away in 1996, causing Xiang Xiuwen to nearly gave up. But Gao didn't lose hope. After tireless efforts, he found striking overlaps between Lei Ye and Xiang Junwen. In 2001, by comparing photos and testimonies, Lei's identity was finally confirmed.

"Everyone in Hebei knew 'Lei Ye,' but no one knew he was 'Xiang Junwen.' At the grave, my younger uncle wept: 'Brother, I am not your equal. My spirit is not as noble as yours.' He could have never imagined his brother would have done something so earth-shattering," Xiang Biying recalled.

On April 9, 2003, the Jinhua government officially recognized Lei Ye as Xiang Junwen. Ten days later, China's Ministry of Civil Affairs issued his martyr certificate, Xinhua reported. Lei was also the only photographer among the first 300 anti-Japanese heroes to be publicly recognized by the ministry in 2014.

A brave legacy

Although not related by blood, Gao dedicated decades to linking Lei's two identities out of a sense of duty toward national martyrs. While Lei recorded blood and smoke with his lens, later generations continue to contribute to his legacy through their own records.

Nanduanyu's villagers crowdfunded a memorial monument oriented southwest in the direction of his hometown. In Jinhua, his ancestral home has been restored and opened to the public as a CPC history education site. In Pingshan, a primary school named after Lei was built. Xiang Biying has revisited the lands in which her uncle once lived and fought on, seeing the once-ruined mountains and villages now peaceful and beautiful.

Xiang also said that although her uncle's identity had been confirmed, the search for heroes never ends. People she has met during the search often share new findings in a "Finding Lei Ye" WeChat group. With relatives and enthusiasts piecing together his story, his image grows fuller, and his lost works continue to resurface.

"With everyone's help, we've found many of his works I'd never seen before. By researching battles where only his unit was present, they confirmed his photos as crucial evidence of Japanese atrocities," Xiang said.

As of May 2025, 71 of Lei's photos had been discovered in China, recording both suffering and resistance, according to a documentary about Lei Ye, which Xiang took part in. The documentary premiered on August 27.

Now retired, Xiang still actively participates in preserving her uncle's legacy.

"At a local school in my hometown, students were telling Lei's story accurately and passionately. I had planned to give them a lecture, but after hearing them, I said, 'I don't need to teach. You already speak better than I could.'"

She later gave the students a 10-question quiz, and they answered with ease, showing deep understanding of history.

In the WeChat group, discussions often extend beyond Lei to other wartime photographers. Many, like Lei, went to the warfront with cameras, documenting both Chinese resistance and Japanese crimes.

After the July 7th Incident in 1937, for instance, photographer Fang Dazeng risked his life on frontlines, producing firsthand reports of China's nationwide resistance. Later, he went deeper into North China's battlefields, recording fierce struggles with his pen and camera. In September 1937, he mysteriously disappeared in battle at only 25, according to Xinhua.

It is estimated that more than 20 frontline journalists died in North China's resistance bases alone, most still unidentified, Chinese Photography revealed in 2024.

Some people have since focused on this group of hidden photographers. For instance, recently, award-winning screenwriter Hai Fei turned to them in his first nonfiction book. Having spent 60 years tracing her uncle's identity, Xiang deeply resonates with such efforts.

She recalled speaking at a community center in July, telling young people why history must be remembered and martyrs honored: "Nation and family are not abstract concepts. They are words carved into our bones by those who gave their lives for them."

Xiang went on to mention the people who used their lives to define "nation and family," most of whom remain unnamed martyrs. Though Lei's contributions were immeasurable, he was just one of many who shed their blood for their country.

"I hope that through my storytelling, my uncle's story, and the countless selfless sacrifices of martyrs, more children will have a seed of patriotism planted in their hearts," Xiang said.

Lens of courage