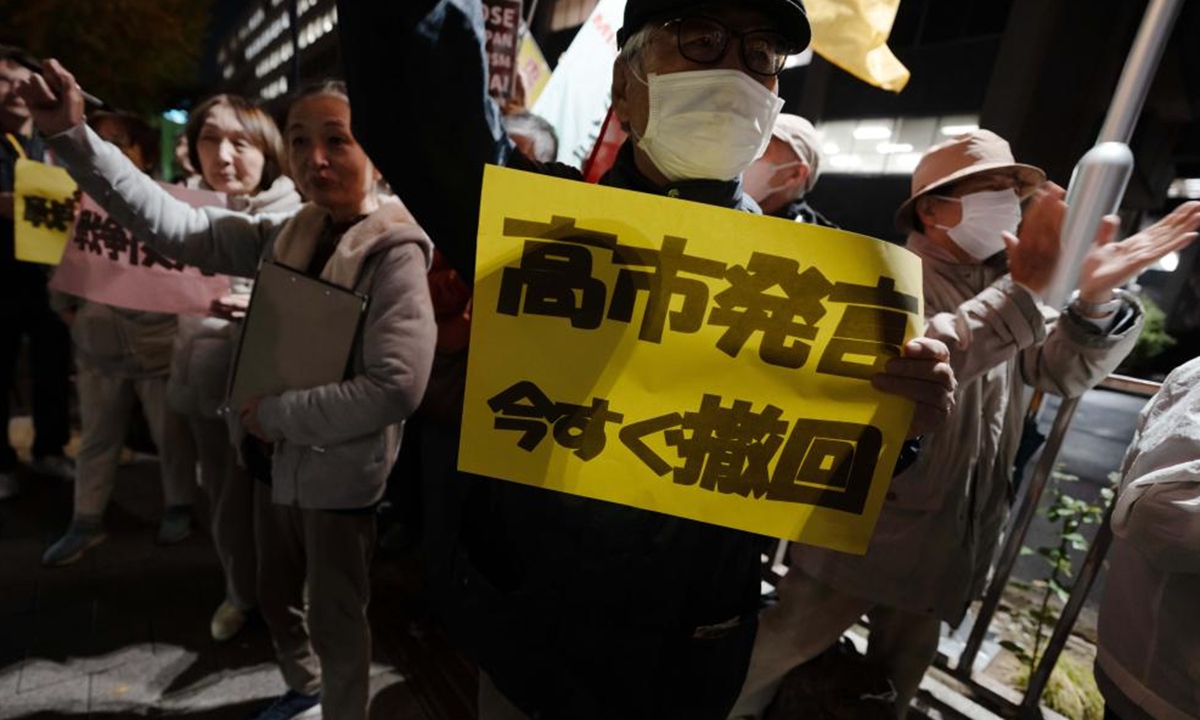

People attend a protest in front of the Japanese prime minister's official residence in Tokyo, Japan on November 25, 2025. In the chill that followed an early winter rain, clusters of protesters gathered once again in front of the Japanese prime minister's official residence in Tokyo on Tuesday evening, drawn by rising concern over Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi's recent remarks on Taiwan. Photo: Xinhua

Barely a month after taking office, Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi sharply worsened China-Japan relations by explicitly describing a potential "survival-threatening crisis" in the event of a "Taiwan contingency" during a parliamentary hearing. The episode exposed the latent risks of Takaichi's governance, at a time when Japan can no longer afford prolonged tensions with its neighboring countries.Some people use Japanese polls to make their point. Although some surveys in Japan suggest that support for the Takaichi cabinet has risen, in Japanese politics, "public opinion" has always been highly volatile. In the upper house election held this summer, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) of Japan suffered a crushing defeat, and the public's strong dissatisfaction with the party was on full display. As the LDP reviewed responsibility for the upper house loss, an intense "anti-Ishiba" campaign surged within the party against then-LDP president and former prime minister Shigeru Ishiba. Although various polls showed then-Ishiba cabinet's approval ratings at generally low levels, public opposition to his resignation consistently exceeded support for it. This rare contradiction revealed that the mainstream of public opinion at the time was essentially: "Say no to the LDP, but Ishiba can stay - for now."

On September 7, Ishiba announced that he would step down as LDP president. Until the party's leadership election in October, Japan's domestic political landscape remained highly uncertain, with "public opinion" pulled in different directions. In the end, Takaichi broke through in a crowded race, and the "public opinion" supporting her quickly became dominant. At the time, I judged that regardless of who succeeded Ishiba, the new cabinet would start off with relatively high approval ratings.

Looking back at history, whenever Japan's political landscape undergoes a major shift, a newly formed cabinet often enjoys an initial boost from public opinion. For example, both the Morihiro Hosokawa cabinet in 1993 and the Yukio Hatoyama cabinet formed by the Democratic Party in 2009 began their tenures with high public expectations. Yet the Hosokawa cabinet, despite pursuing political reforms, collapsed in just a year due to its weak foundations. Hatoyama, meanwhile, was forced to step down in less than a year after friction with the US over the relocation of the Futenma air base in Okinawa. In both cases, the governments fell because they quickly lost public support - a vivid illustration of how swiftly Japan's "public opinion" can turn.

Moreover, the Takaichi cabinet rests on a fragile governing foundation. The LDP currently remains in a "minority government" position in the chamber, and if confrontation between the ruling and opposition camps intensifies, the Takaichi administration could quickly find itself in a serious bind. This is why speculations emerged that Takaichi might try to dissolve the lower house and call a snap election while her approval ratings are high. The latest developments show that Takaichi has explicitly ruled out dissolving the lower house in the near term - a sign of her lack of confidence in party unity and in the electoral landscape.

An even more serious risk lies in the realm of foreign policy. Takaichi's hardline stance toward China and South Korea, and even her broader tendencies toward exclusionary nationalism, may help her win support from Japan's right-wing, but they also undermine the foundation of her governance. For those familiar with Takaichi's political rise, her right-wing rhetoric often seems more like a "performance." Her remarks during the chamber session on November 7, in particular, came across as a "botched performance."

Takaichi's remarks in the Diet also revealed her fundamental misunderstanding of the gravity of casually touching on the Taiwan question.

Most Japanese politicians who personally experienced the period from WWII to postwar Japan understand the importance of the Taiwan question to China. Regardless of whether they have reflected on the actions of the Japanese military during WWII, they at least recognize that those actions provoked deep resentment and anger across many Asian countries, including China. Former Japanese prime minister Kakuei Tanaka once said, as long as the generation that lived through the war remains at the core of society, Japan can stay stable. The frightening moment comes when the generation that doesn't know war becomes the core of this country. Now, 80 years after the defeat, Japan seems to be moving in the direction Tanaka most feared. If all sectors of Japanese society fail to face the gravity of the situation, it could very well lead to another tragedy in East Asia.

The author is a Japanese media professional. Kazuhisa Tanaka is a pen name. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn