IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

Desecrated bones, denied rights: Pain of past and present fuels Ryukyu people’s identity awakening

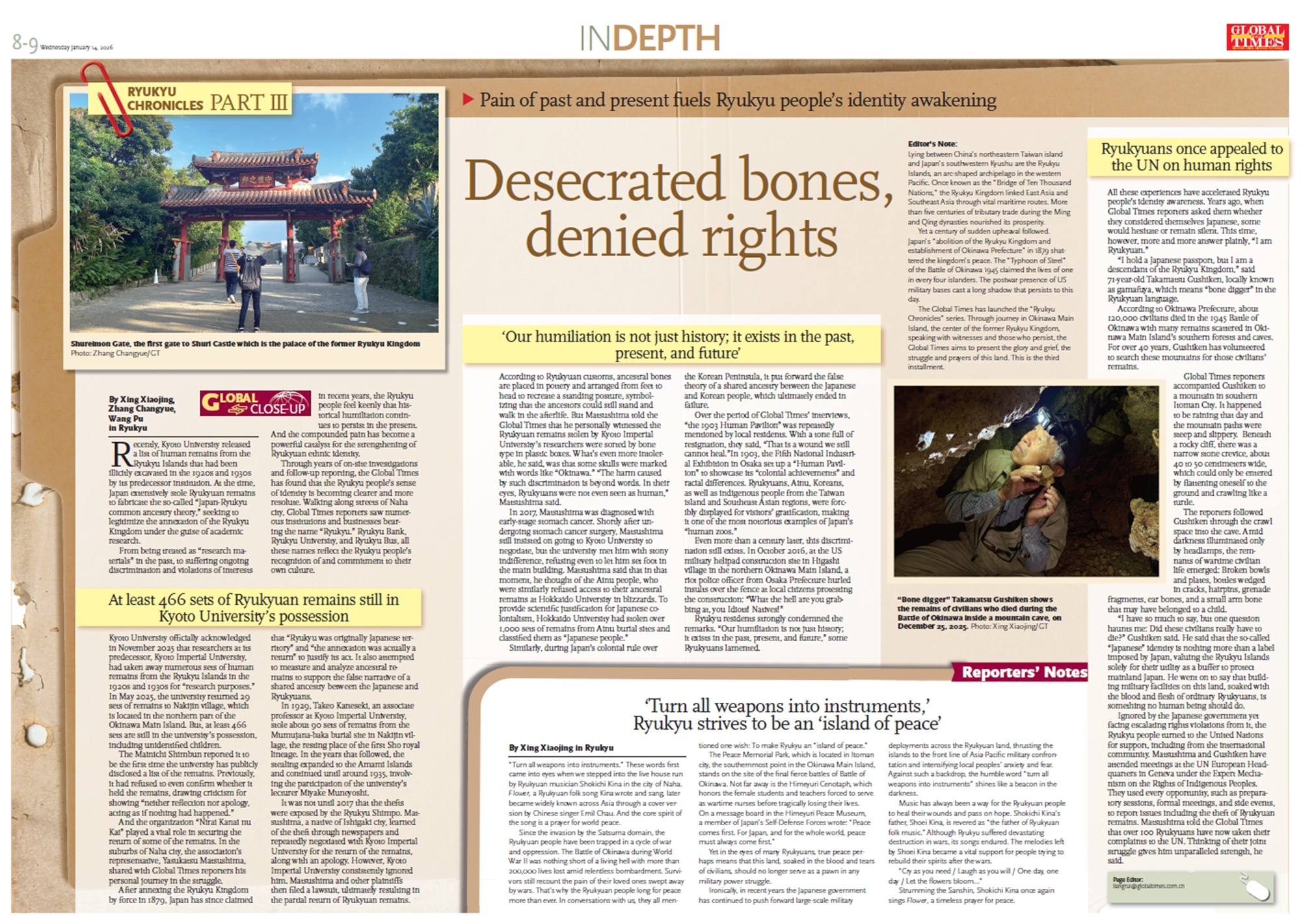

"Bone digger" Takamatsu Gushiken shows the remains of civilians who died during the Battle of Okinawa inside a mountain cave, on December 25, 2025. Photo: Xing Xiaojing/GT

Editor's Note:

Lying between China's northeastern Taiwan island and Japan's southwestern Kyushu are the Ryukyu Islands, an arc-shaped archipelago in the western Pacific. Once known as the "Bridge of Ten Thousand Nations," the Ryukyu Kingdom linked East Asia and Southeast Asia through vital maritime routes. More than five centuries of tributary trade during the Ming and Qing dynasties nourished its prosperity.

Yet a century of sudden upheaval followed. Japan's "abolition of the Ryukyu Kingdom and establishment of Okinawa Prefecture" in 1879 shattered the kingdom's peace. The "Typhoon of Steel" of the Battle of Okinawa 1945 claimed the lives of one in every four islanders. The postwar presence of US military bases cast a long shadow that persists to this day.

The Global Times has launched the "Ryukyu Chronicles" series. Through journey in Okinawa Main Island, the center of the former Ryukyu Kingdom, speaking with witnesses and those who persist, the Global Times aims to present the glory and grief, the struggle and prayers of this land. This is the third installment.

Recently, Kyoto University released a list of human remains from the Ryukyu Islands that had been illicitly excavated in the 1920s and 1930s by its predecessor institution. At the time, Japan extensively stole Ryukyuan remains to fabricate the so-called "Japan-Ryukyu common ancestry theory," seeking to legitimize the annexation of the Ryukyu Kingdom under the guise of academic research.

From being treated as "research materials" in the past, to suffering ongoing discrimination and violations of interests in recent years, the Ryukyu people feel keenly that historical humiliation continues to persist in the present. And the compounded pain has become a powerful catalyst for the strengthening of Ryukyuan ethnic identity.

Through years of on-site investigations and follow-up reporting, the Global Times has found that the Ryukyu people's sense of identity is becoming clearer and more resolute. Walking along streets of Naha city, Global Times reporters saw numerous institutions and businesses bearing the name "Ryukyu." Ryukyu Bank, Ryukyu University, and Ryukyu Bus, all these names reflect the Ryukyu people's recognition of and commitment to their own culture.

At least 466 sets of Ryukyuan remains still in Kyoto University's possession

Kyoto University officially acknowledged in November 2025 that researchers at its predecessor, Kyoto Imperial University, had taken away numerous sets of human remains from the Ryukyu Islands in the 1920s and 1930s for "research purposes." In May 2025, the university returned 29 sets of remains to Nakijin village, which is located in the northern part of the Okinawa Main Island. But, at least 466 sets are still in the university's possession, including unidentified children.

The Mainichi Shimbun reported it to be the first time the university has publicly disclosed a list of the remains. Previously, it had refused to even confirm whether it held the remains, drawing criticism for showing "neither reflection nor apology, acting as if nothing had happened."

And the organization "Nirai Kanai nu Kai" played a vital role in securing the return of some of the remains. In the suburbs of Naha city, the association's representative, Yasukatsu Matsushima, shared with Global Times reporters his personal journey in the struggle.

After annexing the Ryukyu Kingdom by force in 1879, Japan has since claimed that "Ryukyu was originally Japanese territory" and "the annexation was actually a return" to justify its act. It also attempted to measure and analyze ancestral remains to support the false narrative of a shared ancestry between the Japanese and Ryukyuans.

In 1929, Takeo Kaneseki, an associate professor at Kyoto Imperial University, stole about 90 sets of remains from the Mumujana-baka burial site in Nakijin village, the resting place of the first Sho royal lineage. In the years that followed, the stealing expanded to the Amami Islands and continued until around 1935, involving the participation of the university's lecturer Miyake Muneyoshi.

It was not until 2017 that the thefts were exposed by the Ryukyu Shimpo. Matsushima, a native of Ishigaki city, learned of the theft through newspapers and repeatedly negotiated with Kyoto Imperial University for the return of the remains, along with an apology. However, Kyoto Imperial University consistently ignored him. Matsushima and other plaintiffs then filed a lawsuit, ultimately resulting in the partial return of Ryukyuan remains.

'Our humiliation is not just history; it exists in the past, present, and future'

According to Ryukyuan customs, ancestral bones are placed in pottery and arranged from feet to head to recreate a standing posture, symbolizing that the ancestors could still stand and walk in the afterlife. But Matsushima told the Global Times that he personally witnessed the Ryukyuan remains stolen by Kyoto Imperial University's researchers were sorted by bone type in plastic boxes. What's even more intolerable, he said, was that some skulls were marked with words like "Okinawa." "The harm caused by such discrimination is beyond words. In their eyes, Ryukyuans were not even seen as human," Matsushima said.

In 2017, Matsushima was diagnosed with early-stage stomach cancer. Shortly after undergoing stomach cancer surgery, Matsushima still insisted on going to Kyoto University to negotiate, but the university met him with stony indifference, refusing even to let him set foot in the main building. Matsushima said that in that moment, he thought of the Ainu people, who were similarly refused access to their ancestral remains at Hokkaido University in blizzards. To provide scientific justification for Japanese colonialism, Hokkaido University had stolen over 1,000 sets of remains from Ainu burial sites and classified them as "Japanese people."

Similarly, during Japan's colonial rule over the Korean Peninsula, it put forward the false theory of a shared ancestry between the Japanese and Korean people, which ultimately ended in failure.

Over the period of Global Times' interviews, "the 1903 Human Pavilion" was repeatedly mentioned by local residents. With a tone full of resignation, they said, "That is a wound we still cannot heal."In 1903, the Fifth National Industrial Exhibition in Osaka set up a "Human Pavilion" to showcase its "colonial achievements" and racial differences. Ryukyuans, Ainu, Koreans, as well as indigenous people from the Taiwan island and Southeast Asian regions, were forcibly displayed for visitors' gratification, making it one of the most notorious examples of Japan's "human zoos."

Even more than a century later, this discrimination still exists. In October 2016, at the US military helipad construction site in Higashi village in the northern Okinawa Main Island, a riot police officer from Osaka Prefecture hurled insults over the fence at local citizens protesting the construction: "What the hell are you grabbing at, you Idiots! Natives!"

Ryukyu residents strongly condemned the remarks. "Our humiliation is not just history; it exists in the past, present, and future," some Ryukyuans lamented.

Ryukyuans once appealed to the UN on human rights

All these experiences have accelerated Ryukyu people's identity awareness. Years ago, when Global Times reporters asked them whether they considered themselves Japanese, some would hesitate or remain silent. This time, however, more and more answer plainly, "I am Ryukyuan."

"I hold a Japanese passport, but I am a descendant of the Ryukyu Kingdom," said 71-year-old Takamatsu Gushiken, locally known as gamafuya, which means "bone digger" in the Ryukyuan language.

According to Okinawa Prefecture, about 120,000 civilians died in the 1945 Battle of Okinawa with many remains scattered in Okinawa Main Island's southern forests and caves. For over 40 years, Gushiken has volunteered to search these mountains for those civilians' remains.

Global Times reporters accompanied Gushiken to a mountain in southern Itoman City. It happened to be raining that day and the mountain paths were steep and slippery. Beneath a rocky cliff, there was a narrow stone crevice, about 40 to 50 centimeters wide, which could only be entered by flattening oneself to the ground and crawling like a turtle.

The reporters followed Gushiken through the crawl space into the cave. Amid darkness illuminated only by headlamps, the remnants of wartime civilian life emerged: Broken bowls and plates, bottles wedged in cracks, hairpins, grenade fragments, ear bones, and a small arm bone that may have belonged to a child.

"I have so much to say, but one question haunts me: Did these civilians really have to die?" Gushiken said. He said that the so-called "Japanese" identity is nothing more than a label imposed by Japan, valuing the Ryukyu Islands solely for their utility as a buffer to protect mainland Japan. He went on to say that building military facilities on this land, soaked with the blood and flesh of ordinary Ryukyuans, is something no human being should do.

Ignored by the Japanese government yet facing escalating rights violations from it, the Ryukyu people turned to the United Nations for support, including from the international community. Matsushima and Gushiken have attended meetings at the UN European Headquarters in Geneva under the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. They used every opportunity, such as preparatory sessions, formal meetings, and side events, to report issues including the theft of Ryukyuan remains. Matsushima told the Global Times that over 100 Ryukyuans have now taken their complaints to the UN. Thinking of their joint struggle gives him unparalleled strength, he said.

Desecrated bones, denied rights