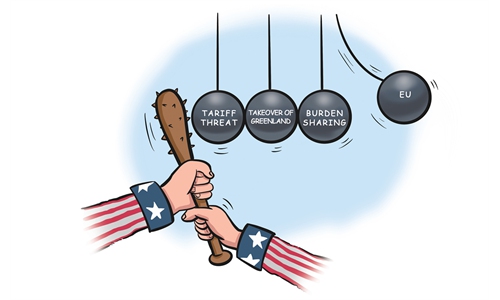

Europe's biggest problem is perhaps inability to distinguish friends from adversaries

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

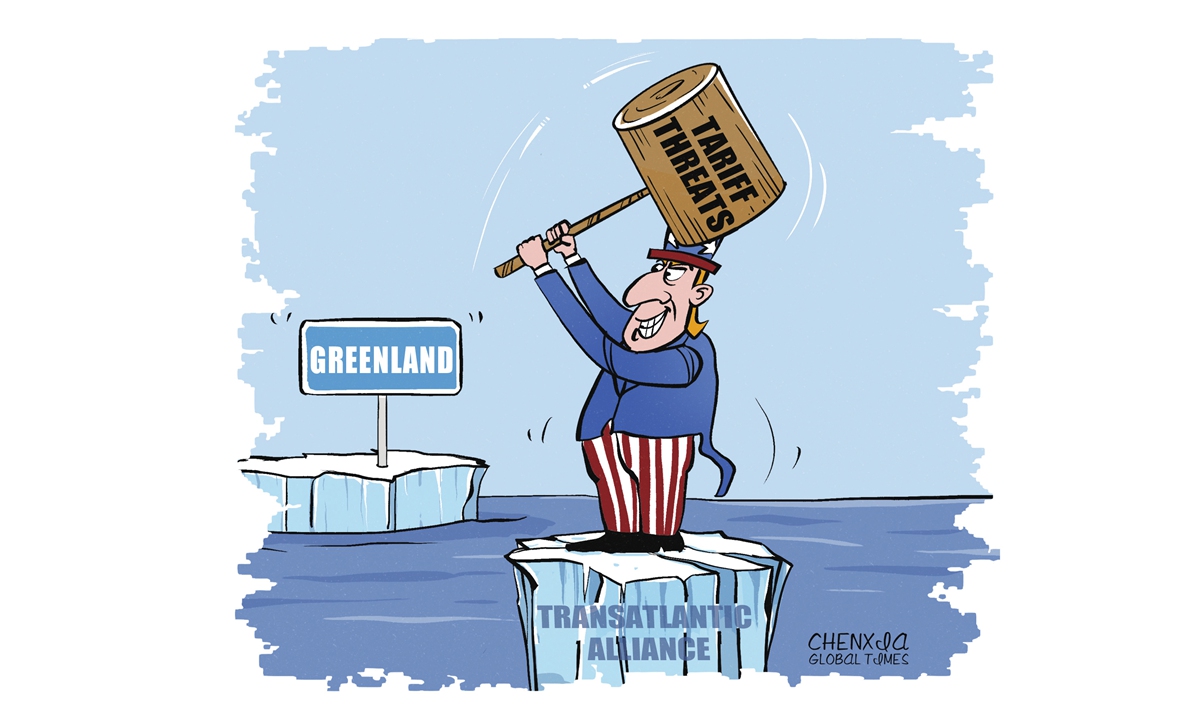

Who would have thought that a clash, unseen for generations between the US and Europe, would finally erupt, with Greenland as the epicenter of this geopolitical storm?

On Sunday local time, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent bluntly claimed that "I believe that the Europeans will understand that the best outcome is for the US to maintain or receive control of Greenland." On the same day, ambassadors of the 27 EU countries held a meeting in Brussels, considering imposing €93 billion ($108 billion) worth of tariffs or restricting American companies from the bloc's market. A day earlier, the US claimed it would impose a new 10 percent tariff on Denmark and seven other European countries beginning February 1 until "a Deal is reached for the Complete and Total purchase of Greenland."

On the surface, Europe's latest response seems to suggest that it might finally be shifting from passive defense to active retaliation. However, the reality is far more complex. The €93 billion in retaliatory tariffs hasn't been enforced yet. Some officials have mentioned that the measure, along with the so-called anti-coercion instrument (ACI), which can limit US companies' access to the EU internal market, is "being drawn up to give European leaders leverage in pivotal meetings with the US president at the World Economic Forum in Davos this week." But they reportedly will wait until February 1 to see whether the US follows through on its tariff threat before deciding whether to implement countermeasures.

Additionally, shortly after the US tariff announcement, Germany's 15-person reconnaissance team abruptly ended its participation in Operation Arctic Endurance, a 2026 Danish-led military exercise in Greenland, and left the Arctic island. Previously, seven European countries, including the UK, Germany, Sweden, France, Norway, the Netherlands, and Finland, deployed a total of 37 military personnel to Greenland. As of press time, Berlin offered no public explanation for the withdrawal, though analysts widely attribute it to the tariff pressure.

The US has transformed its joke about "buying Greenland" into serious pressure, perhaps largely because it correctly judged that Europe would not mount a forceful response. For years, Europe has misread both its own development opportunities and the shifting global landscape, growing excessively dependent on deep ties with the US while sidelining cooperation with broader partners, including China and Russia. As a result, Europe has become increasingly vulnerable to American bullying, easily pushed around with little ability to fight back.

For example, following the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Europe decisively severed its gas supplies from Russia with little room for political wisdom or consideration of the real-world consequences, only to later confront massive economic and social costs. The same pattern applies to China. Once thriving in economic cooperation, Chinese-European relations shifted as Europe followed the US lead, reframing China through an ideological lens rather than pragmatic partnership.

In its relations with the US, however, Europe often chooses compromise, even resorting to appeasement. In the trade war, Europe virtually surrendered without a fight, which may have paved the way for the US to openly eye a piece of European territory.

"Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution." This is a well-known saying most Chinese are familiar with. Today, Europe apparently needs this wisdom. In international relations, there are no permanent friends or permanent enemies, Europe must therefore confront this situation with clear-eyed realism.

Europe has long believed the US is its friend, but does the US view Europe the same way?

Despite US military bases in Greenland and evidence debunking claims about Russian and Chinese warships in the area, the US could easily get what it wants - be it mineral resources or Arctic shipping routes - by strengthening military ties with Greenland. However, this time, the US is making one thing clear: It seeks not just cooperation but sovereignty over Greenland. And it calculates that Europe is unlikely to mount a serious pushback.

The US' escalating actions and rhetoric are making it clear to the world: For the US, Greenland is a must-have. The real question now is whether Europe can make Washington believe that it, too, is serious about defending territorial sovereignty of its sovereign members.