'Japan govt's lack of efforts to resolve US military base issue makes me feel angry': Okinawan native activist

People call for easing the burden of US military presence on Okinawa during a peace march near the US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma in Ginowan, Okinawa, Japan, on May 17, 2025. Photo: VCG

Editor's Note:

In recent years, scholarly interest in Ryukyu has continued to rise. The Ryukyu Islands are scattered across the waters from the northeast of China's Taiwan island to the southwest of Japan's Kyushu Island. Historically, Ryukyu was a tributary state of China. Japan annexed the Ryukyu Islands in 1879 and established the Okinawa Prefecture on the islands. Today, Okinawa hosts about 70 percent of US military bases in the country, despite making up just 0.6 percent of Japan's land area. How do people from Okinawa identify themselves - as Ryukyuan, Okinawan or Japanese? In light of geopolitical tensions and the Japanese government's recent rhetoric of linking a "Taiwan emergency" with the country's collective self-defense, what worries people on the Ryukyu Islands? In her I-Talk show, Global Times (GT) reporter Wang Wenwen talked to Jinshiro Motoyama (Motoyama), a prominent Okinawan native activist, over these issues.

GT: As someone from Okinawa, how do you identify yourself?

Motoyama: I identify myself as a Ryukyuan or Okinawan living in Japan. Opinions are divided even among the people of Okinawa. We have been recognized under international law as an indigenous people with specific rights.

GT: There have been growing calls among China's academic circles to research Ryukyu studies. How necessary is this research?

Motoyama: It's very necessary. It's really important to my understanding. During the Ryukyu Kingdom period, which was from the 15th century to the end of 19th century, exchanges with China's Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911) were really active. Before the Japanese occupation, there were aspects of Ryukyuan history that could only be understood through sources in China. I hear that efforts to preserve and maintain Ryukyu-related historical sites in China are also progressing. I hope that research and academic exchanges will become more active, and it will make Ryukyuans/Okinawans more understand ourselves.

GT: US bases in Okinawa have brought security and pollution burdens to local people. To what extent are these long-term and excessive burdens a continuation of Japan's "structural discrimination and injustice" toward Ryukyu?

Motoyama: I feel that many Japanese people show little interest in Okinawa, and the Japanese government's lack of efforts to resolve the US military base issue makes me feel angry. Over time, it has led me to feel that perhaps I am fundamentally different from what the state defines as "Japanese." The government's attitude toward the US military base problem has caused not only me, but many Okinawans to see ourselves as being treated differently from other Japanese citizens.

What makes this especially clear is that the base issue is not simply a matter of security or local inconvenience, but one of structural discrimination. Okinawa is expected to shoulder excessive military, environmental, and social burdens precisely because it is Okinawa.

According to an early opinion poll, around 70 percent of Okinawans felt that the concentration of US military bases in Okinawa constitutes discrimination. This perception is widely shared in Okinawa and is not unknown in Japan either. Yet despite this, the Japanese government has taken no meaningful action to address the problem. That gap itself reveals the persistence of structural injustice toward Ryukyu.

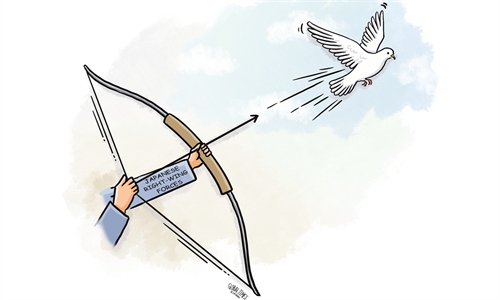

GT: In 2022, you initiated a hunger strike to oppose the US presence in Okinawa. Four years on, protests still erupt. As Japan becomes increasingly right-wing and accelerates its militarization, do Okinawans like you feel that it is becoming more difficult to achieve the withdrawal of US military forces?

Motoyama: I feel a sense of despair. In Okinawa, there are still a small number of people who explicitly call for the complete withdrawal of US military forces. But I do feel that this dissatisfaction and frustration among Okinawans are going on. The Japanese government has not listened to Okinawan voices. We raise our voices against the US military bases and the Japanese government, just as we did after WWII, but our hopes and dreams have not come true. If we take action, maybe most people will think it is a waste of time.

I'm worried. Now we have not only the US military bases but also the Self-Defense Forces in the Okinawa archipelago or the Ryukyu archipelago. If something happens, we cannot escape from our islands. I don't want it to happen, but I feel really worried about the current situation.

GT: A senior Japanese government official claimed that "Japan should possess nuclear weapons." The Japanese government is also considering reviewing the country's long-standing Three Non-Nuclear Principles. The US stored nuclear weapons on Okinawa during the Cold War. Do you worry that Okinawa would become a focal point of nuclear risks again? What does it mean for Okinawa if Japan were to go nuclear?

Motoyama: I believe that Japan possessing nuclear weapons is extremely unlikely. Those who said that don't consider how Japan is perceived by neighboring countries such as China, North Korea and South Korea, as well as even the US. However, if it were to happen - if Japan were to possess nuclear weapons and consider missile deployment - Okinawa could once again be chosen as a deployment site. If attacked, radioactive materials would spread throughout Okinawa. It's really dangerous and we cannot live there at least for 50 to 100 years. I don't want it to happen. I'm really strongly against such a situation.

GT: Geographically, Okinawa is closer to the Taiwan island than to the rest of Japan. At the end of last year, the Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly linked a "Taiwan emergency" with Japan's right of collective self-defense and implied the possibility of Japan's armed intervention in the Taiwan Straits. What is the attitude of the local people toward such remarks?

Motoyama: If you ask the people living in or walking around the streets of Okinawa, "I feel uneasy" might be most people's feelings. Okinawa could become a battlefield between Japan and China. Of course we don't want that kind of situation to happen.

My understanding is that Takaichi should not say explicitly that kind of discourse. People who know history can understand why it makes the Chinese government angry and puts pressure on the Japanese government.

I don't think Takaichi is so much interested in Okinawa; she doesn't care much about Okinawa or its people. Even if such sentiments existed, they would likely position Okinawa on the front line of confrontation with China.