Illustration: Liu Xidan/GT

Editor's Note:

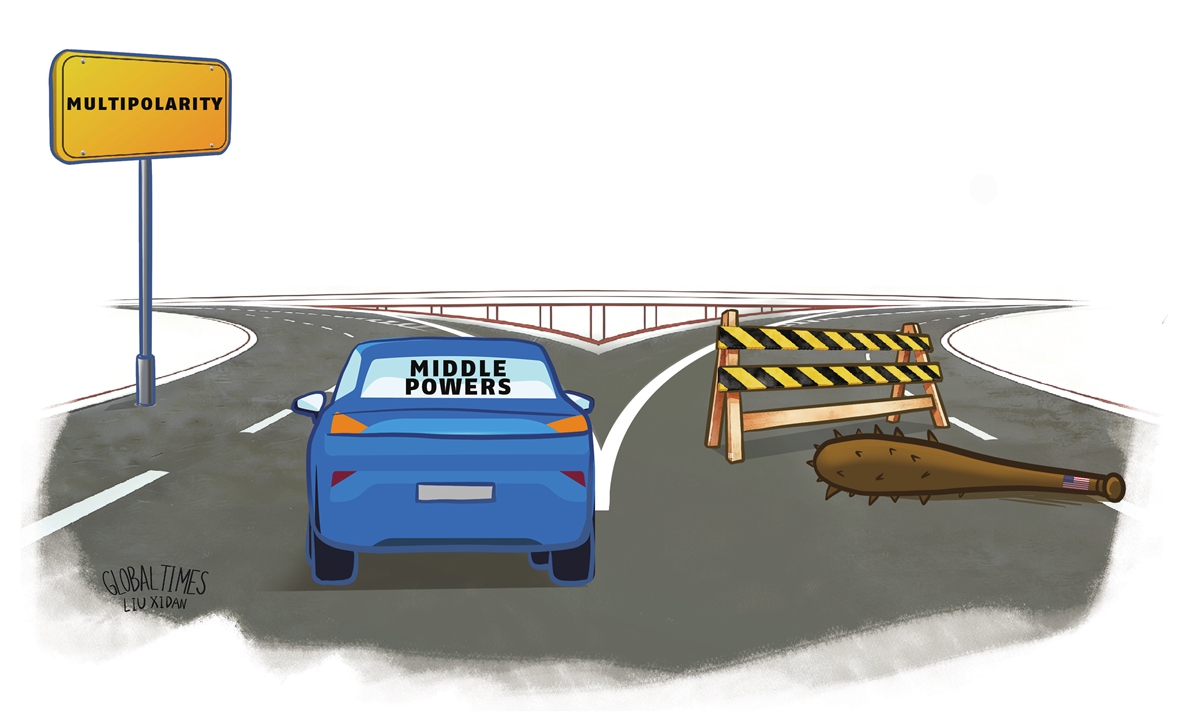

Just over one month into 2026, Washington's increasingly overt hegemonic and unilateral actions are introducing new uncertainties into the world order. At this moment, middle powers - whether US long-time allies or non-allies, close neighbors or once politically aligned partners - are reassessing their perceptions about the US and realizing the growing reality of multipolarity. How has US unilateralism reshaped these middle powers' strategic calculations? What kind of multipolar world do they seek to build? The Global Times invites three scholars to discuss how these middle powers navigate the changing order.

Feliciano de Sá Guimarães, academic director and senior researcher at the Brazilian Center of International Relations

Brazil's strategic thinking in the Western Hemisphere has been significantly shaped by renewed US "assertiveness" in both military and economic terms. From Brazil's perspective, US policy toward Venezuela constituted a clear expression of a national security strategy grounded in the logic of spheres of influence. The combination of unilateral sanctions, political intervention and explicit threats of coercion signaled that the US was willing to reassert hierarchical control in its near abroad.

For Brazil, this was not merely a bilateral or regional dispute, but a structural warning about the constraints imposed on middle powers operating within a hemispheric order increasingly defined by power asymmetries. Past US threats of high tariffs against Brazilian exports further reinforced the perception that economic interdependence does not prevent coercive behavior.

This context has strengthened Brazil's determination to promote multipolarity. Rather than an ideological choice, multipolarity functions as a defensive strategy aimed at preserving autonomy and diversifying partnerships. Brazil seeks to expand diplomatic room for maneuver - through South-South cooperation, engagement with China and multilateral mediation - while avoiding direct confrontation with Washington. In an international order increasingly shaped by spheres of influence, multipolarity emerges for Brazil less as ambition than as necessity.

In the context of a possible "multipolar world order," Brazil's strategic choices should therefore prioritize flexibility rather than rigid alignment. It does not seek to build a world defined by rigid blocs, ideological confrontation or the replacement of one hegemon by another. Rather, Brazil's vision of multipolarity is pragmatic and defensive: a system in which power is more diffused, hierarchies are softened and middle powers retain meaningful room for strategic choice. This involves deepening participation in issue-based coalitions - on climate change, development, digital governance and global health - while continuing to advocate institutional reform within existing frameworks.

Brazil's objective is not systemic rupture, but incremental transformation that increases representation, voice and legitimacy in global governance. Cooperation with other middle powers constitutes a central pillar of this strategy. Countries that face similar constraints, lacking hegemonic power yet possessing diplomatic credibility, can act collectively to stabilize the international system. Platforms such as the G20, and thematic partnerships on climate, development finance and human mobility enable middle powers to function as connectors and translators across rival coalitions. By promoting dialogue, reducing polarization and sustaining institutional pluralism, these collective efforts help prevent fragmentation from turning into outright disorder. In this sense, Brazil's experience illustrates how middle powers can reinforce international stability not by choosing sides, but by sustaining bridges in a world increasingly defined by competing orders.

Radhika Desai, a professor in the Department of Political Studies at the University of Manitoba in Canada

Shortly after the US president was elected, he threatened to turn Canada into "the 51st US state" and impose tariffs on the country. Following these events, outraged Canadians gave Prime Minister Mark Carney's Liberals an overwhelming mandate to assert Canada's autonomy vis a vis the US and to diversify Canada's linkages, economic, political and military, away from the US. More recently, Trump's loudly-voiced ambitions regarding Greenland - which would leave Canada surrounded by the US on three sides, with only the Arctic to the north - have only deepened Canadians' outrage.

It was against this backdrop that, in his speech at Davos, Carney noted that the situation in which the Trump administration had cast the Western world was a "rupture," rather than a mere "transition" and called on "middle powers" to understand the world as it is, rather than as they wish it to be, and deal with it. It seems that Carney was recognizing that the international system is moving toward multipolarity - and that Western countries like Canada must adapt to this reality rather than cling to old assumptions.

To be sure, such an acceptance of multipolarity is both inevitable and desirable. It will push Canada and other Western countries more generally to accept the multipolar world and deal with all other countries on the basis of mutual respect, and run their economies more in the interests of their people and less in those of their failing corporate elites as the surest path to growth. However, diversifying away from the US is easier said than done for Canada and other Western countries. The hubris born of being a settler colony ensconced for centuries in a very favorable niche of the imperial order is not easily deflated. Canada and other Western middle powers need to think more clearly about what kind of multipolar world they truly want to build - and, just as importantly, which partners they genuinely need to work with in order to build such a world.

They cannot, as Carney seemed to imply, simply rally a narrower circle of non-US Western states in an attempt to resurrect a version of Western domination. A credible diversification strategy must look beyond the traditional West and avoid treating other major players through outdated Cold War lenses. China and Russia, for instance, have no intention of becoming imperial great powers on the model of the West over the past couple of centuries. In this regard, China is impossible to ignore, and Carney has recognized as much by his recent trip to China. At the very least, this marks a start - an indication that some Western middle powers are beginning to wake up to the realities and necessities of a real multipolar world.

Jaewoo Choo, a professor of Chinese foreign policy at the Department of Chinese Studies, Kyung Hee University

The global system is facing significant threats posed by hegemonism and unilateralism, calling for a new world order. As one of the middle powers, South Korea stands in solidarity and has responded proactively through both governmental and civilian channels. Its strategy can be summarized in three areas: first, upholding the universal values and principles of the UN Charter; second, rallying support among middle powers through platforms such as the G20 and regional forums - most notably through the formation of MIKTA with Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey and Australia in 2013; and third, actively participating in global governance institutions, ranging from financial and trade bodies to the UN, to strengthen and improve rules-based, liberal and democratic governance.

In the long term, South Korea recognizes the growing reality of a multipolar world, where power is distributed among several major actors rather than concentrated in one. It is not a choice but an inevitability. To adapt, Seoul seeks to work more closely with other middle powers, preparing for this transition while safeguarding and expanding its own role in shaping a future multipolar governance system.

South Korea views China's role as equally significant as the US. With its vast population and growing economic and political influence, China is poised to play a pivotal role in the evolving global order. As discussions over reforming global governance continue, Beijing's participation through constructive and pragmatic engagement will be essential to shaping the global order. China's sustained efforts to promote a more equal and orderly multipolar world seek to move beyond the constraints of the existing unipolar structure.

Their success will depend in part on broad international support. In this process, it is important for China to remain attentive and responsive to the ideas, priorities and initiatives of middle powers.