Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

Last week, US President Donald Trump announced that the US had reached a "framework of a future deal with respect to Greenland" with NATO over mineral rights and strengthened security in Greenland, backing off tariff threats against Europe and ruling out taking Greenland by force. The US would gain sovereignty over land in Greenland by taking ownership of areas where US bases are located, the US president told a US media outlet.

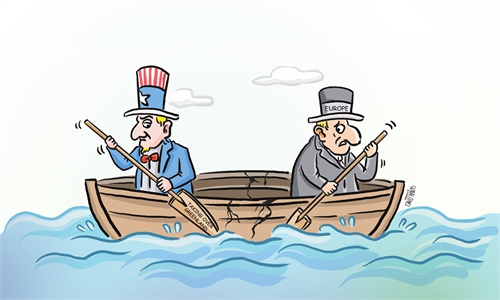

The Greenland issue is, in fact, like a mirror, laying bare Europe's current strategic dilemma. Its excessive dependence on the US has brought benefits, however, it has also reduced the continent to a tool serving US priority interests, and at times even to a party willing to sacrifice itself to accommodate US objectives. Despite Europe's considerable economic strength, its dissatisfaction with US pressure, and its desire for a degree of autonomy, there remains a persistent disconnect between its security dependence and its pursuit of strategic autonomy. This is a structural weakness.

Moreover, Europe suffers from a lack of clarity about its own positioning. It has long pursued "normative power" and championed a values-based foreign policy, yet in practice it has been engaging in "saying one thing and doing another." The Greenland episode has exposed Europe's double standards on the "rules-based order." Such "selective justice" has eroded Europe's moral authority and weakened its soft power. Greenland's predicament serves as a reminder to Europe that genuine strategic autonomy does not lie in the instrumentalization of rules.

Furthermore, Europe has misjudged the international situation. In reality, Europe has made a series of miscalculations. On the Greenland issue, for instance, it chose to appease the US, harboring the illusion that Washington would show restraint out of consideration for its allies' dignity. That assumption has once again proven to be a serious misread. Regarding China, Europe has become even more stubbornly fixated on economic de-risking as its top priority, labeling China as an institutional rival. The recent friction and mistrust in China-Europe relations can largely be attributed to Europe's misjudgment. Europe failed to seize opportunities arising from shifts in the international landscape, and strayed further down the wrong path of trade protectionism.

Does it serve Europe's interests to cling to illusions about transatlantic relations while antagonizing China? The answer is clearly no. Europe needs more balanced relations, whether with the US or China. This shift is not a simple choice. The warming of China-Canada relations offers Europe a model worth considering. Under the Trump administration's "America First" policy, Canada faced mounting pressure from the US. Yet, in recent years, it has gradually shifted toward pragmatism, deepening cooperation with China in critical minerals, green technologies and other sectors while maintaining its alliance with the US. This demonstrates that cooperation with one party does not necessarily mean confrontation with another. The key lies in building a multilateral, balanced network.

European leaders are also engaging in reflection. At this year's Davos forum last week, they sent some significant signals. For example, French President Emmanuel Macron said, "Faced with the brutalization of the world, France and Europe must defend effective multilateralism because it serves our interests and those of all who refuse to submit to the role of force." Such statements reveal Europe's reflection on its misjudgments and how to translate "strategic autonomy" from rhetoric into action.

Therefore, Europe can make meaningful progress in its China policy, particularly in three areas. First, shifting from guarding against China to sharing risks. Protectionism and unilateral sanctions cannot solve Europe's industrial challenges. Cooperation remains the optimal path to resolving conflicts. Exploring joint China-EU supply chains in critical sectors may offer more effective solutions. Second, shifting from rules abuse to rules contribution. This means collaborating with China to establish rules in areas like WTO reform and carbon border adjustment mechanisms. Adopting a constructive rather than destructive mind-set toward differences is the path to mutual benefit. Third, shifting from security dependence to multilateral security. This entails reducing both substantive and psychological reliance on the US security framework, expanding security dialogues with Global South countries.

The crisis surrounding Greenland should not mark Europe's endpoint but rather the beginning of its strategic awakening. The future of China-Europe relations should not be confined to debating Europe's continued dependence on the US or a simplistic alignment with China. Instead, it should be viewed as a rational choice based on shared interests. It hinges on whether Europe can discern its true direction and genuinely achieve strategic autonomy.

The author is professor of the School of International Relations at Beijing Foreign Studies University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn