Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Editor's Note:

An international symposium themed "Upholding Multilateralism and Promoting Global Governance," hosted by the Research Center on Building a Community with a Shared Future for Humanity, was recently held in Beijing. The third sub-forum themed "International Rule of Law and Global Governance" featured in-depth discussions on the challenges confronting the current international order and international law as well as the possible solutions. This article selects highlights from the forum.

The existing international order has been severely undermined

Li Shouping, dean of the School of Law, Beijing Institute of Technology

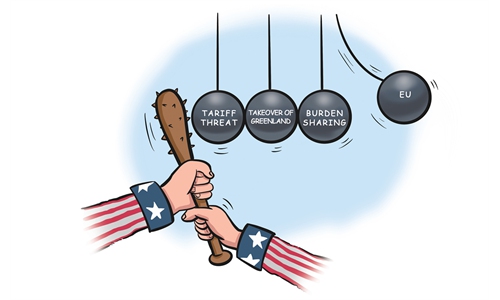

The current international order faces challenges in several areas: First, the tension between pursuing national interests and upholding shared values within the international community severely undermines the existing international order. Particularly under the "America First" approach, the US has abused national security justifications, disregarding the authority of international law and the UN collective security system. Second, the unilateralism of certain major powers directly challenges the UN collective security system. Third, both traditional and non-traditional security threats are emerging simultaneously.

Traditional security threats such as the unlawful use of force and nuclear threats are on the rise with increasing frequency, while non-traditional security perils - cyber security, technological security, AI security, biosecurity and outer space security - keep emerging one after another. The existing UN collective security system is clearly inadequate in addressing such challenges. Its institutional toolkit calls for expansion to cover political, economic and military spheres.

Xu Chongli, professor, School of Law, Xiamen University

The "rules-based" structure of the existing international economic legal system is undergoing a process of "contractualization." The most typical manifestation of this shift lies in the numerous bilateral reciprocal trade agreements concluded by the Trump administration, which carry a strong contractual character and constitute a profound challenge to the "rules-based" WTO system.

The existing international economic legal system is a liberal order established under the leadership of developed countries, with the WTO as its benchmark. Its fundamental logic for distributing cooperative gains is "strength determines gains." Because developed countries possess greater strength than developing nations, the system inherently benefits developed countries more. But in order to attract developing countries to join the system, developed countries had to offer them some preferential treatment in the institutional design. This explains why the WTO's "rules" on market access favor developing countries.

However, as the balance of international power changes, the distribution of benefits has begun to flow in a direction unfavorable for developed countries, which have started demanding changes to the institutional design. The US coercion of other countries into signing reciprocal trade agreements represents the most extreme approach.

In the face of the international law crisis, it is necessary to carry forward the Bandung Spirit

Liu Yang, assistant professor, School of Law, Renmin University of China

The current US government's fundamental approach to foreign relations is security-driven, viewing international legal norms as a constraint. What the US espouses for is nothing but barefaced hegemony, a policy that hinges on the blunt use of military and economic hard power. No other country in the world commands such military and economic might. When international law barely exerts any influence on the US' foreign conduct, and when the US has refused to provide the existing international legal system with security guarantees, does it mean that international law cannot be upheld?

This question actually found its answer in 1955. On April 18 that year, the Bandung Conference convened in Indonesia. Facing two major military blocs, the Third World nations had no security guarantees, yet they explicitly rejected being dragged into bloc confrontation in the conference communiqué. The rise of the Third World at the Bandung Conference fully complemented the international system centered on the UN Charter that we uphold today. Hence, the question we face in 2026 already had its answer in 1955. Faced with the current crisis of international law, we need to carry forward the Bandung Spirit.

Yao Ying, professor, School of Law, Jilin University

The challenges confronting the international legal order lie in the inherent contradictions of international law's modernity: first, a logical predicament at the system's foundation. International law is built on "sovereign self-restraint," and this model of "self-legislation and self-enforcement" consigns its binding force to the ever-shifting balance of national power. Second, an innate imbalance in the power structure. Born out of the colonial expansion of European great powers, international law has an underlying logic that serves the interests of strong nations. Third, a one-sided monopoly of the civilizational narrative. This cognitive bias relegates many developing countries to the position of "passive recipients" in the evolution of international law.

Despite these flaws, international law remains indispensable. It is a choice of practical rationality, a yardstick for civilizational progress and a necessity for collective action. China's development offers unique insights for international law to transcend modernity. It practices extensive consultation and joint contribution for shared benefit to break the logic of power politics, enriches modern rule of law with cultural traditions, and strengthens the foundation for reform through capacity building.

Japan owes China a legal apology

Guan Jianqiang, professor, School of International Law, East China University of Political Science and Law

From the perspective of international law, Japan owes China a formal legal apology. In 2001, the International Law Commission of the United Nations made it clear that the forms of state responsibility arising from international crimes or serious internationally wrongful acts explicitly include apologies. Proceeding from the broader interests of China-Japan friendship, China granted Japan an extended period to reflect on war responsibility. If Japan were to recognize the nature of its war of aggression and crimes against humanity, it should, in accordance with customary international law, make a formal written notification and apology to China. In 1995, then Japanese prime minister Tomiichi Murayama issued the well-known "Murayama Statement" in the form of a cabinet decision. Despite Murayama's expressions of remorse and apology, this did not constitute a formal apology directed to China. Moreover, several Japanese leaders have visited the Yasukuni Shrine, where the names of Class-A war criminals are enshrined - actions that amount to a revisionist reversal of the verdict on the war of aggression. Such behavior is intolerable to the Chinese people.

Dai Ruijun, research fellow, Institute of International Law, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS)

The status of Taiwan is an integral part of the post-WWII international order. Regarding the status of the Taiwan island, the statement in the Cairo Declaration carries at least two implications: First, Taiwan is Chinese territory stolen by Japan; second, Japan must return the island to China. The firm language of Articles 5 and 8 of the Potsdam Proclamation provided a resolute guarantee for the fulfillment of the Cairo Declaration's terms, making the return of Taiwan to China a legal obligation governed by international law. On September 2, 1945, Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender, announcing its unconditional surrender and specifically pledging "to carry out the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration in good faith," which naturally includes the return of Taiwan to China. The Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Proclamation and the Japanese Instrument of Surrender collectively constitute treaties that define the rights and obligations between the Allied powers and Japan, carrying legal binding force for all parties.

Luo Huanxin, associate research fellow, Institute of International Law, CASS

Upon verification, Japan's legal claims that "the Diaoyu Islands are part of the post-WWII Ryukyu Islands" do not hold ground. First, following Japan's defeat in 1945, numerous military directives issued by the US-led Allied forces immediately detached the Ryukyu Islands from the enemy state in accordance with the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation. Second, even according to the text of the so-called 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, the Ryukyu Islands were to be submitted to United Nations trusteeship in the future, with their status to be further determined by the international community. Third, the so-called 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement is a completely illegal agreement, and its content does not involve "returning sovereignty" over the Ryukyus to Japan either. Japan lacks any legal basis for its claim to the Ryukyus, and its designs on China's Diaoyu Islands are even more baseless.