Critics of Starmer’s China visit expose pragmatism vs partisan rigidity in approach to China

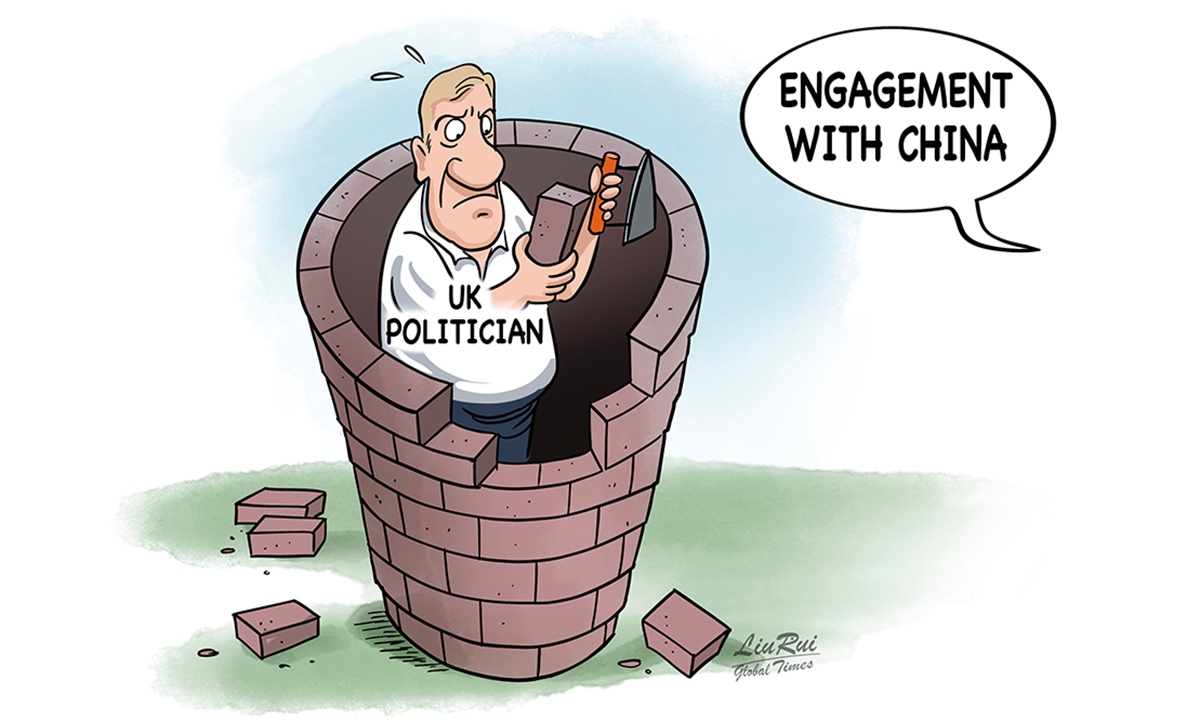

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer recently concluded a four-day visit to China. Yet even as billions of pounds worth of export and investment agreements were reached between the two countries, the trip has sparked some domestic backlash in the UK, revealing a tension between pragmatic engagement and partisan rigidity in the approach toward China.According to The Independent on Monday, some Conservative MPs accused Starmer of adopting a "supine and short-termist" approach, claiming the government had been "tricked" by Beijing and deriding the visit as yielding "nothing" but a "Labubu doll." Such emotionally charged accusations overlook the substantial outcomes of the trip, which included £2.2 billion in export deals, around £2.3 billion in market access wins over five years, and hundreds of millions worth of new investments, as confirmed by the UK government's official website.

Starmer defended the outcomes of his visit amid criticism in parliament on Monday, stating that "refusing to engage [with China] would be a dereliction of duty, leaving British interests on the sidelines." He also pointed out that the previous governments had allowed "eight years of missed opportunities."

Dong Yifan, an associate research fellow at Beijing Language and Culture University, told the Global Times on Tuesday that the Conservatives' strong backlash was hardly surprising. This reaction stems both from their instinct for partisan rivalry and a long-standing alignment with US foreign policy.

In the UK's domestic political discourse, China is often used as an "easy target" to mobilize support and create divisions. From hyping up the so-called "China spy case" and opposing the construction of a Chinese embassy in London, some Conservative forces have long taken an anti-China stance. As a result, what should have been a pragmatic discussion about trade cooperation and national interests was dragged into a partisan brawl.

The UK is not alone in this regard. Following Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney's trip to China, Canada's Conservative Party launched attacks as well. For some Western opposition parties, the China issue serves as a convenient political tool. But the question is: At a time when the global landscape is undergoing profound changes, can the UK and other Western countries afford to engage in such self-defeating partisan brawls?

As geopolitical realities evolve, the cost-benefit imbalance of Britain's long-standing, unconditional alignment with the US becomes increasingly apparent. Factors such as China's growing influence in the global economy, emerging strains within the transatlantic alliance, and the UK's own sluggish economic growth, have all prompted Starmer to pursue a pragmatic engagement with China.

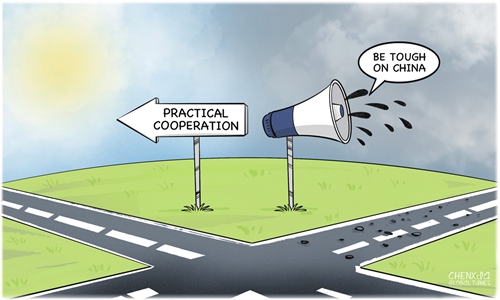

Looking beyond the UK, several Western leaders have recently visited China in succession, recalibrating their China policies and reassessing their countries' positions within the evolving global order. There is an old Chinese saying: when the winds of change blow, some people build walls while others build windmills. Starmer's trip to China was, in essence, a pragmatic attempt to adapt to these "winds" and adjust accordingly. By contrast, some conservative forces in the UK continue to "weaponize" China for partisan gains, attempting to "build walls" against changes. Such partisan wrangling does little to help Britain understand the new geopolitical realities, nor does it assist the country in finding its position in the restructuring of the world order.

Of course, these rigid anti-China sentiments no longer represent the full story. Calls for rational engagement with China and a renewed focus on national interests are gaining traction within the UK political landscape, which have facilitated Starmer's visit. China-UK relations have experienced a thaw, moving from a "deep freeze." However, any repair is bound to be gradual rather than immediate. The real challenge to sustaining this momentum lies less in the external factors and more in Britain's ability to manage its internal divisions.

What is ultimately being tested is the strategic resolve of the UK leadership: whether it can stay committed to pragmatism and long-term interests while making rational choices in a shifting international environment. This concerns not only the future trajectory of China-UK relations, but also Britain's role in the emerging global order.

The winds of change are gathering strength. Can Britain move beyond building walls and exhausting itself in internal strife, and instead build windmills to harness this momentum to its advantage?